Protein Solvation Thermodynamics: The Unfolding Equilibrium (ENGLISH VERSION)

An introduction to the change in structural stability of proteins induced by physicochemical means. For a Japanese version click here.

Introduction & Purpose

Upon preparing a lecture about my research given to Kawanishi-Midoridai Senior High School, I was requested to present some simple websites in English and Japanese which could prepare the students for the upcoming lecture. While I am incapable to judge Japanese websites on their ability to describe my research due to huge gaps in my Japanese language skills, I failed to find satisfactory websites in English due to the content being too far from the relevant topic, the level being way too high, and most commonly the presumption that the reader was already familiar the basics of chemical thermodynamics and protein chemistry. Because a lot of science is incremental science and encourages multidisciplinary science it is usually hard to provide rigorous explanations without a broad background. However, here I take it upon myself to write about the topic “Protein Solvation Thermodynamic” in hopefully sufficiently simple terms. After all, Albert Einstein is famously quoted as having said “If you can’t explain it simply you don’t understand it well enough”. Thus in this text, we will cover how protein structure is affected by physicochemical effects using simple models and basic protein chemistry. However, before we begin, I like to state this text is dedicated to Kawanishi-Midoridai Senior High School, which I am looking forward to visiting on December 14, 2022.

Proteins: A Polymer Consisting of 21 Different Amino Acid Monomers with Different Properties

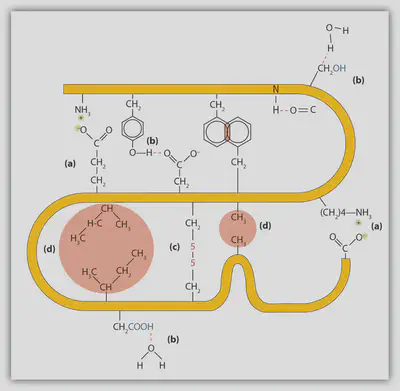

Proteins are large biomolecules that are composed of amino acids joined together. While all the amino acids share the property of possessing an amino group and a carboxylic acid group, the 21 most common proteinogenic amino acids are unique due to their side chain which is attached to the α-carbon. Because the side chain mainly determines the properties of the amino acids, the amino acids can be categorized based on various properties. The most common properties for categorization include polarity, hydrophobicity, charge, aromatic/aliphatic carbon skeleton, and volume occupation. In the creation of proteins, the individual amino acids are joined via a peptide bond, a covalent bond. Due to the peptide bond being equivalent to the amide group, the atoms participating in the bond are all found in the same plane due to the partial double-bond character of the peptide bond.

Stabilizing Interactions in Proteins

While the polymer is kept together by strong covalent peptide bonds, the 3-dimensional structure of a protein is mainly determined by a large set of weak interactions. Because the polymer contains a great amount of rotational freedom, the interaction between residues can usually be attributed to either local interactions or nonlocal interactions. Local interactions are interactions between closely neighboring amino acid residues in the amino acid sequence, with examples of such interactions being found in helices and turns. Nonlocal interactions in contrast are interactions occurring between amino acid residues that are not adjacent in the amino acid chain sequence. Note these terms do not comment on the residues’ separation in space, but on their separation in the amino acid sequence. Whether an interaction between two amino acid residues is long-ranged or short-ranged is mainly depending on the kind of interaction occurring between the two residues. Thus in the following, we will shortly review the interactions that contribute to stabilizing the native fold of proteins.

Hydrophobic Interactions: Oil-Water Separation

The hydrophobic effect is perhaps best recognized from the phase separation of water and oil, which is traditionally attributed to the unfavourability of mixing polar and non-polar molecules. Even though the hydrophobic effect is a complicated phenomenon and has for a long time been an active topic of research, it is now evident that the hydrophobic effect is a consequence of water-water hydrogen bonding and waters’ orientation around non-polar solutes. Put simply and slightly oversimplified, water hydrogen bonding is so strong that water would rather interact with other water molecules than solvating the non-polar solute. This implies that the non-polar solute molecules will position themselves such that it minimizes their exposure to water, by for example the formation of oligomers or for elongated solutes to collapse upon themselves, thus allowing water to maximize water-water interactions.

In the context of proteins, the hydrophobic effect is commonly viewed as the first step in protein folding. In specific, many amino acid residues possesses hydrophobic (non-polar) side chains, rendering the amino acid more likely of attempting to exclude water. To exclude water from hydrophobic amino acid residues, proteins usually bury their hydrophobic residues within the interior of the protein by collapsing on themselves, also called the hydrophobic collapse.

Electrostatics Interactions: Long-Ranged Correlations

While partial charge describes the charge associated with the individual atoms, we use the word “ion” to describe the total non-zero formal charge of molecules and atoms. In the case of proteins, we talk about the charged/ionic amino acid residues which possess the ability to carry the formal charge of either +1 (histidine, arginine, lysine) or -1 (aspartate, glutamate, cysteine, selenocysteine, tyrosine). The charge of these amino acid residues is gained from the gain and removal of protons with the behavior governed by classic acid-base chemistry.

Electrostatic interactions between point charges are described by the Coulomb law, which states the electrostatic energy between two point charges decays with $1/r$, where $r$ is the separation between the two charges. Due to this long-ranged force, proteins are commonly found to engage in a highly complicated network for electrostatic interactions throughout the protein which can stabilize the folded state.

Hydrogen Bonding & Salt Bridges: Strong Polar Contacts

Hydrogen bonding is a combination of multiple factors which together form a highly strong intermolecular bond. In specific, there are two contributions in the form of electrostatic interactions and orbital overlap (bond covalency). A hydrogen bond occurs when a hydrogen-bonded donator group, such as an amide, -N-H, shares its hydrogen with an acceptor group, such as carbonyl oxygen, O=C-, thus leading to the hydrogen bond having the characteristic form D-H···:A, where D is the donor, A is the acceptor possessing an electron lone pair and ··· is the though-space interaction between the donor and accepted mediated by the hydrogen, H.

In folded proteins, a vast amount of hydrogen bonds are found, mainly among the backbone carbonyl groups and amide groups. The hydrogen bonds between these groups are the main stabilizing force found in α-helices and β-sheets, making up the secondary structure of proteins.

Due to hydrogen bonds having part electrostatic character, the “hydrogen bond strength” depends on the environment surrounding it. While the dielectric constant in water is around 80, the dielectric constant in the protein interior is estimated to be 2-12 thus much more oil-like.

A special case of the hydrogen bond occurs when the donor (D) and acceptor (A) are charged, having the form D⁺-H···:A⁻. This special case is in protein chemistry called a salt-bridge. A charged donor could for example be the ammonium group found in the side chain of lysine or the guanidino group found in the side chain of arginine. A charged acceptor in proteins could for example be found in the carboxylate group in the side chain of aspartate and glutamate. This interaction is even stronger than a hydrogen bond due to added electrostatic strength due to the charges but is also pH dependent.

van der Waals Interactions: Tight Packing Using Nonpolar Contacts

Van der Waals interactions are responsible for the tight packing of proteins with a fraction of space filled inside a protein being around 74% being the same value as the most efficient packing of identical spheres. However, proteins are not perfectly packed, as we do observe internal protein dynamics. Instead, proteins obtain such a high packing fraction due to the different sizes and shapes of the amino acid side chains.

The Statistics of Protein Folding - Why do Proteins Fold?

From the previous discussion of the interactions, it should now be clear that the heterogeneity of the amino acids yields the possibility for the protein to interact strongly with itself. Consequently, the sequence of amino acids (the primary structure) is of great importance in determining the structure formed by proteins. However, there are many ways a protein can interact with itself, so why do proteins tend to adopt a specific three-dimensional structure? To answer this question we will use a combination of statistics, which deals with the probability of events occurring, and thermodynamics, which deals with the flow of heat and energy and spontaneity of processes. This combined discipline is called statistical thermodynamics and is the foundation for my research. Using statistical thermodynamics we will now demonstrate why proteins fold and unfold under various conditions, however, let us start by looking at how probability and thermodynamics connect.

Probability and Thermodynamics: Statistical Thermodynamics

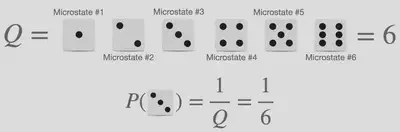

Probability calculations in their most simple form are something we all encounter at some point in our life, however, statistical thermodynamics complicates it slightly by the introduction of the words microstate and partition function however the words can be explained by comparing to something tangible: The probability of obtaining specific values when rolling dice as illustrated in the image below.

The word microstate within the analogy of dice refers to one of the possible outcomes when rolling the dice. As such a 6-sided dice has 6 microstates, whereas a 20-sided dice has 20 microstates. The word partition function, donated $Q$, can best be explained using the Danish translation “tilstandssummen” which translates to “the sum of states”. Within our dice analogy, thus refers to the total number of states the dice contain. Using these words it should then be obvious that the probability of a microstate, observing a specific number from a die, is given as the ratio of the weight of observing the specific microstate, being equal to 1, and the partition function, which is the total number of the possible outcome. From this example, it is obvious that all microstates possess the same probability equal to 1/6.

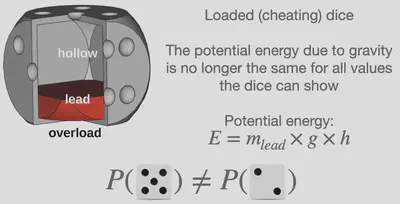

However, Ludwig Boltzmann, the founder of statistical thermodynamics, discovered that microstates of different energy do not possess equal probability. Within our dice example, this would for example be the case if one uses a dice that is unequal in mass on all sides (loaded dice), such that the potential energy due to gravity is different for the various numbers shown by the dice. The equation which determines the probability of a microstate is called the Boltzmann distribution. While the mathematics may still be slightly complicated, the main message to take away is the following: The probability of a microstate depends on its energy and the temperature of the system. The applications includes a great variety of systems; from the description of dice (fair and loaded) to the description of atoms and molecules.

Lattice Statistics of Proteins: The HP Model

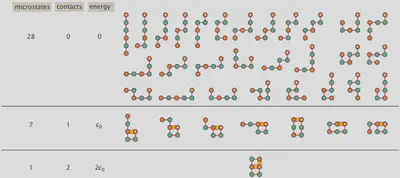

Having covered some of the fundamentals of statistical thermodynamics, we are now ready to address protein folding. To do so we will use the so-called “hydrophobic-polar (HP) protein folding model” which reduces the number of amino acids from 21 to 2 with the two amino acids only being different from each other by one residue being hydrophobic (H) capable of intermolecular interactions like van der Waals interactions and the other residue being polar (P) being incapable of forming intermolecular interactions with other adjacent residues. Modeling the whole amino acids as single spheres on a lattice, we can conduct a self-avoiding walk, to find all possible configurations the protein can adopt. Using the sequence “HPPHPH” the microstates possible have been visualized below

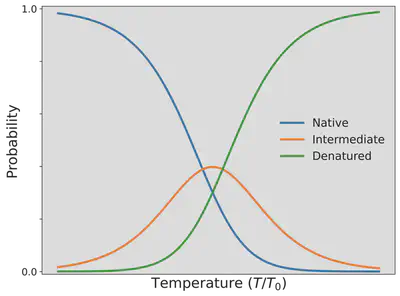

Since the probability depends on the temperature $T$, the probability of the folded/native state $P_{\mathrm{N}}$ having 2 HH contacts, the probability of the intermediate state $P_{\mathrm{I}}$ having 1 HH contact, and the probability of the unfolded state $P_{\mathrm{D}}$ having no HH contacts has been visualized as a function of the temperature below.

As we can see the protein goes from high to lower probability in finding the folded, native state as we increase the temperature with the unfolded, denatured state instead becoming predominant. You can now explain why the egg proteins, ovalbumen, and ovotransferrin, found in egg-white change from a transparent, water-soluble substance to a white, water-insoluble substance as we boil an egg for our ramen.

Outlook and My Research: Cellular Conditions Does Not Equal Pure Water

In the previous, we have seen that proteins’ tendency to fold and unfold depends on temperature. However, this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are many more effects that affect the proteins’ structural stability, including pH, pressure, crowding, co-solvents, and other proteins. Additionally, proteins possess many equilibria which are important for correct biological functioning, with protein folding/unfolding being just one of them.

Biologically relevant environments which possess high variability in terms of the previously mentioned physicochemical properties are not hard to find, with perhaps the most obvious example being the inside of a cell in the cytoplasm. To get a feeling of the highly complex and crowded environment inside a cell, I can highly recommend watching this video by the RIKEN research institute in Japan.

Like one of the goals mentioned in the video, my research seeks to understand how proteins behave under various influences. Using this knowledge, we may one day understand how to engineer proteins to work under arbitrary conditions and even optimize them to work in a highly complex environment like the inside of cells. Using molecular simulations conducted on supercomputers I hope that my research will contribute to not only advancing the basic science of protein chemistry but also that we may put the knowledge to use to design drugs in the fight against diseases and design molecules for industrial purposes to the benefit of humankind.